All about periods. For those who get a period and those who don’t.

Period basics

- What you need to know. Period.

- Let’s talk about periods

- Period basics

- From menarche to menopause

- Period perspectives

What’s a “normal” period?

- How to track a cycle

- What does a period feel like?

- What’s “normal” period pain?

- What is endometriosis?

- Speak up for your health needs

Period products: there’s a lot to choose from

Period symptoms: what helps?

Periods are a part of life

Ways to learn more

Welcome! We’re glad you’re here.

We developed this workbook to help raise awareness and break down taboos about periods and related health issues like endometriosis. This information is for everybody, not just for people who get a period.

This workbook can be used in all kinds of settings and contexts, from classrooms, to youth groups, libraries, to health, community, and learning centres, to name just a few. The content is designed for a wide range of youth (ages 8-18) and can be adapted to suit different groups and settings.

What you need to know. Period. is all about getting people talking. It’s not a secret that some of us get a period, but there is a lot of mystery and misinformation out there about menstruation. Let’s put an end to the secrecy now. Period.

What you need to know. Period.

This workbook is for everybody: for those who get a period, those who will eventually get a period, and those who never will. There’s a lot to know! But don’t worry, this workbook is full of information, activities, and ways to continue your learning.

Together, we’re going to start an honest conversation about menstruation. It’s a big step toward breaking down taboos and stigma about periods. And our period talks will include all people who get their period, because you can’t tell if someone gets a period just by looking at them.

Words you need to know. Period.

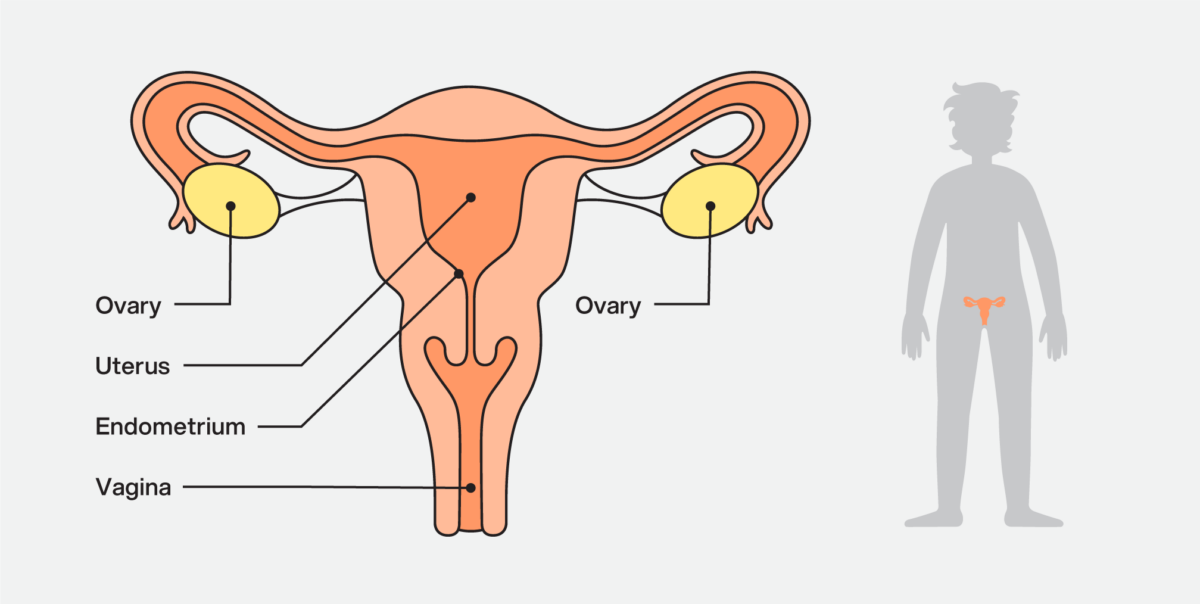

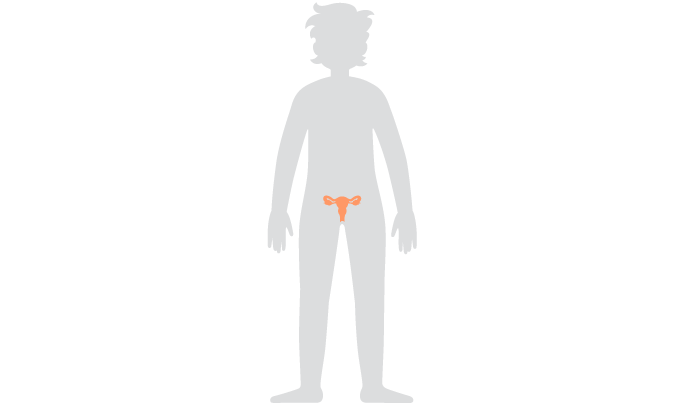

Menstruation is often called a period because it’s the period of time each month when a person with a uterus bleeds. The uterus is a triangle-shaped space in the body where a baby can grow during pregnancy. Most periods last anywhere from 3-8 days and happen once a month.

A person with a uterus could be a:

- cisgender girl or woman

- trans, non-binary, or two-spirit person

- person assigned female at birth (AFAB)

- intersex person

Taboo is something that a group of people or even whole societies and cultures avoid talking about because it may be seen as offensive, dangerous, or impolite.

Stigma is a negative way of thinking and talking about something that makes people uncomfortable.

Cisgender (cis) is someone who identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender (trans) is someone whose gender doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth. For example, a trans boy is someone who was assigned female at birth but who knows themself to be a boy.

Non-binary person is someone whose gender blends aspects of being a man or a woman, or a gender that is different from being a man or woman.

Two-spirit is a pan-Indigenous term for someone who has both a female and male spirit. Some Indigenous peoples view two-spirit as a third gender or something in between female and male. It is a cultural, spiritual, gender, and sexual identity for some.

Intersex is someone born with a body that doesn’t fit into the traditional binary boxes of female or male. They may have both female and male organs and/or hormones. Almost 2% of the population is born intersex. Being intersex is a naturally occurring variation.

Here’s what we’ll learn:

- Why is it important for everyone to learn about periods?

- What is a period? Who gets them and why?

- What is it like to have a period? When will it start and stop?

- What is a normal period? When should you ask for help?

- Why are periods a secret?

- Ways to manage and track periods

Having a period is a normal, healthy part of life for many people. A period is a vital sign or baseline of health for someone who gets their period. It’s something that doctors and nurses usually ask about at a check-up.

Getting a first period is part of puberty. Most people go through puberty, whether they get a period or not. Even though most of us will go through puberty eventually, many people don’t talk about it or ask their questions. Keeping it a secret can feel lonely and can lead to feelings of shame and embarrassment about what you’re experiencing. But you don’t need to feel this way! The first big step is to talk about it. It can be a powerful and freeing thing for everyone, not just for those who get their period.

Here are some helpful words we can use to talk about periods:

- A period

- Having or getting a period

- Menstruation or menstrual cycle

- Menstruating

- Bleeding

- A cycle

- Moontime

- Flow

Q: Are there any other helpful or positive words we can use to talk about periods that you’ve heard before that you would add to this list?

Q: What are some words that are unhelpful or harmful when talking about periods?

Q: Why is it harmful to use negative terms to talk about periods?

Q: Look at the list of positive period words on the previous page. Which words can we agree to use together to talk about periods? Can we all agree to not use any of the negative terms?

Q: Why is it important for everyone, not just people who get their period, to learn about periods?

Here are some ideas:

- To develop empathy and compassion for our own experience and the experiences of others

- To be an advocate for our own health and the health of the people we care about

- To recognize how periods are presented in the media and choose to think and talk differently

- To be a source of support to people who get a period

- To understand the impact of periods on gender equality, poverty, and the environment

Q: What else would you add to this list? Work as a group to add your own answers.

Having a period is part of a cycle that’s controlled by hormones in the body. These hormones cause the lining of the uterus to get thicker to prepare the body for a possible pregnancy.

Each month, if a menstruating person doesn’t get pregnant, the lining of their uterus sheds and they’ll bleed from their vagina.

Who can get a period?

Only a person with a uterus and ovaries can get a period. You can’t always tell if a person gets their period just by looking at them.

What’s it like to have a period?

Most periods last between 3-8 days each month. The menstrual cycle is about 27-30 days in total. Some people have shorter cycles and some people have longer cycles. Most people get their period every 21‑35 days, or once a month.

Many people have regular periods, which means they know when to expect to bleed each month, but some people, especially in the early years of menstruation, have irregular periods that can be hard to predict.

With each period, a person can lose around 2-3 tablespoons of blood, but it might look or feel like more.

The way a period feels can be different for each person, because everybody is different.

Some people will experience:

- Cramping in the area below the belly button

- Sore breasts

- Back pain

- Dizziness

- Diarrhea, constipation, or nausea

- Feeling more sensitive emotionally

- Fatigue or tiredness

Not everyone will feel all of these things during their period. And they won’t feel them in the same way as someone else with a period. Most people find having a period uncomfortable, but there are lots of things that can help. We’ll learn about this later on in the workbook.

A menstrual cycle doesn’t last forever. Having a period means that a person may be fertile and could become pregnant from sex or sexual contact. This fertile phase in life can last around 40 years before a person becomes less fertile and their period stops. This is called menopause.

- Can happen between ages 8-16

- You can’t predict when a first period will come, but it usually happens around 2 years after the first signs of puberty (like breast development and growing pubic hair)

- Everybody is different, some people will start to bleed earlier and some later, just like some will start puberty earlier and others later

- Some young people with a uterus will never menstruate, for a number of different reasons, like hormone imbalances, illnesses, eating disorders, being very athletic or underweight

- People with a uterus who haven’t had their period within 3 years of developing breasts may want to speak to a doctor, nurse, or trusted adult

- During the first year of menstruating, periods can be unpredictable and can vary in duration, but this will usually calm down and become more regular over time

- A person’s first-ever period may not look like what we think of as a regular period. The blood might appear very dark (almost brown) and it might be thick, rather than liquid.

- A person’s first period might be short (2-3 days) and it might be light (not much blood), but everybody’s different

- Can happen between ages 40-50

- A person’s period can slow down, become irregular, and hormones can change

- Periods can become lighter or heavier during this phase

- Some people experience uncomfortable or difficult symptoms during perimenopause, like:

- Sleep problems (night sweats, difficulty sleeping, fatigue)

- Hot flashes

- Aches and pains

- Skin problems

- Bladder control problems

- Mood swings

- Memory loss

- Can happen between ages 45-60

- This stage is when a menstruating person hasn’t had a period for 12 months in a row

- It marks the end of the menstrual cycle

- Fertility slows down and eventually stops in this stage

- Everybody’s different: some people will have uncomfortable symptoms during menopause, much like in perimenopause, and some won’t

Let’s talk. Period.

- Why do we all need to know about the different life stages and phases of a period?

- Do you know someone in each of these life stages?

- What are some ways we can support people we know and care about through menarche, perimenopause, and menopause?

Period perspectives

For many, a person’s first period marks an important milestone and life transition. Getting a period can be seen as entering a new stage in life. It’s a big part of puberty and marks a transition from childhood toward adulthood for people who get a period.

Puberty will be a little different for everyone because everybody’s different. There are physical changes that happen during puberty, like getting a period, for example, but there are also changes that affect how we feel, including our mood and emotions. Puberty is a time of growth and change and for some people this time can be challenging. If you or someone you know is struggling, please reach out for help. You can talk to a friend, an adult you trust, or a healthcare professional, like a doctor, nurse, or a therapist.

Different cultures, religions, and peoples have their own views, beliefs, and practices for transitions between life stages, particularly birth, puberty, marriage, and death. While a lot of secrecy surrounds having a period in our Western culture, some cultures celebrate this important time in a person’s life.

- Q: Make a list of some big life changes and milestones.

- Q: What are some of the ways you, your family, and your community mark or celebrate these milestones?

- Q: What are some of the ways you know that other cultures, religions, and peoples mark or celebrate these milestones?

Here are two ways a person’s first period is celebrated by communities, cultures, and peoples:

Let’s talk. Period.

- Look at the examples of celebrations shared in this workbook. What do you notice? How do you think a young person might feel about their period after participating in one of these kinds of ceremonies?

- Have you or someone you know been part of a celebration to mark an important milestone? What was it like?

- How do ceremonies like the ones shared in this workbook shape how we view the big life transitions they mark?

What’s a “normal” period?

Almost everyone will go through puberty eventually. Since everybody is different, everyone’s experience of it will be a little different. Because a period can be an important sign of health or a vital sign in people who get their period, it can be helpful to learn about what’s normal and not normal for most people.

When we use the words “normal” and “not normal” in this workbook, we’re talking about what most people experience. If your experience is different from what’s “normal,” that doesn’t necessarily mean there’s something wrong, or that you should see a doctor. But, your health is important. If you’re worried something might be wrong, speak to an adult you trust. As a group, you might choose to use a different word to describe what’s normal and not normal.

What does a normal period look like for most people?

- Most people’s periods last for about 3-5 days

- Some people’s periods can last for up to 8 days

- How long a period lasts can change over time, especially in the first years of having a period

- About once every month

- Most people’s periods happen every 21-35 days

- To know how long a menstrual cycle is, start counting from the first day of one period to the first day of the next period

- A typical menstrual cycle is about 29 days long

- Having a regular period means that you have an idea of when the next one’s coming

- For example, if a person’s period comes every 27‑30 days, it’s a regular period

- The first couple of years of having a period can be unpredictable, but most people’s periods become more regular over time

- Most people produce around 2-3 tablespoons of blood each period

- Some people have heavier periods (more than 3 tablespoons of blood) and some have lighter periods (less than 2 tablespoons of blood)

- A person’s flow can be heavier in the first and last years of having a period

- Periods can be heavier (a heavier flow) in the first few days of each cycle

- They can be lighter toward the end of each cycle

- The colour of blood can change throughout the cycle (it might be bright red, deep red, or brown at times)

- Having some blood clots (jelly-like clumps of blood) during a period is normal, especially for people who get a heavy period, as long as the clots are smaller than the size of a quarter

How to track a cycle

For people who get a period, learning how to track their cycle can be really helpful. You can learn what’s normal for you by tracking how long your period lasts and how long your cycle is. This information can help you predict and plan for your next period. It’s also something a doctor or nurse should ask about at a check-up because a period is a vital sign of health.

It can be tricky at first to know how to track a cycle, but there are lots of different ways to do it.

A person who gets a period could:

- Use one of the many free or paid online apps for period tracking

- Use a calendar

- Make notes in a journal or diary

There are lots of things we can track when it comes to a cycle:

- How long is the period?

- How often does it come (how long is the cycle)?

- What are the symptoms?

- What are the person’s diet and appetite like?

- What kind of physical activity do they get?

- How much sleep are they getting?

Track a cycle and predict the next period

If you’ve already had your first few periods and remember when you had them, you can do this activity using your own cycle. If you don’t get a period, you can use Andie’s story below to answer the questions in this activity. You can work on your own or with a partner.

Hi, I’m Andie!

I’m 13 years old and I got my first period when I was 10. It took a long time for my period to be more regular and for me to learn when I would get my next one. A little while ago I started tracking my cycle using an app on my phone. It’s pretty easy and super helpful. Now I’m not surprised when I get my period!

Here are Andie’s last 3 periods:

Use the calendars above to answer questions about Andie’s cycle, or use a calendar and your own cycle

as an example.

Q: How long does the period usually last?

Q: How long is the cycle?

Tip: start by counting from the first day of one period and stop counting just before the first day of the next period. The first day of bleeding is always day 1 of the cycle. Hint: Andie’s first cycle is 28 days long.

Q: When will the next period be? If you did this activity using Andie’s cycle, point to the first day of the next expected period on the calendar to the right. If you’re using your own cycle as an example, write your own answer on a piece of paper.

Tip: you could use a calendar app on your phone to find the dates.

Q: Why is it helpful for someone who gets their period to track their cycle?

What does a period feel like?

The menstrual cycle is controlled by a number of hormones in the body. We all react a little differently to hormones. Some people find that their mood, emotions, and overall mental health are affected by their period. It can be helpful to recognize patterns in mood related to a cycle, to be able to plan ahead and get support.

For some people, symptoms happen before their period and can be very difficult. This is called Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS). PMS can affect a menstruating person’s body, mood, and behaviour.

Body symptoms:

- Sore breasts

- Bloating

- Headaches

- Abdominal cramps

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Back pain

- Low energy

- Food cravings

Mood & behaviour:

- Irritability

- Anxiety

- Difficulty focusing

- Sadness

- Anger

- Not wanting to talk to anyone

People who get their period might also have some of these symptoms during their period. If you’re worried about how you’re feeling, it’s a good idea to track your symptoms and speak to a trusted adult about making an appointment to see a doctor. There are also lots of ways to help yourself or someone you know feel better before and during a period. We’ll learn more about those a little later on in the workbook.

Q: What do you or someone you know who gets their period experience each month? Looking at the body outline below, write down where you have physical symptoms. Write down the kinds of emotional symptoms you have. If you don’t get your period, you can do this activity thinking about someone you know who gets their period.

- Q: Why is it important to be aware of mental health symptoms like mood and emotions as well as the physical symptoms of a period?

- Q: How do you know when you should reach out to someone for help with difficult emotions?

- Q: Who could you reach out to when you need help with your difficult emotions?

- Q: How can you help someone you care about when they’re having difficult emotions?

What’s “normal” period pain?

Most people will feel some discomfort or even pain before and during their period. Some discomfort is normal. Some people have very little pain with their period and others have very difficult periods. This can make it tricky to know when to ask for help. Your body is very smart and if you learn to listen to it, you’ll get to know your body best.

Ways to tell if period pain is not normal and you should see a doctor:

- Taking an over-the-counter painkiller like Advil, Tylenol, or Midol doesn’t help

- The pain regularly keeps you from going to school and doing your regular activities

- You regularly vomit, have diarrhea, or are constipated during or around your period

- You regularly bleed through a pad, tampon, or period underwear in less than 2 hours

- You feel like something’s wrong and you want to get help

If any of these are true for you, you may want to speak with a doctor, nurse, parent, or elder in your community. Remember: only you know what it feels like to be in your body. You know your body best.

In this workbook, we’ve explored some of the physical symptoms people can have before and during their period. Some of these are pretty normal, and some might be signs of a more serious health condition, like endometriosis, Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB), Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS), Adenomyosis, or Fibroids.

Because it’s one of the most common period-related conditions, we’re going to focus on endometriosis (en-doh-meetree-oh-sis).

Endometriosis, sometimes called endo, is a disease that affects at least 1 in 10 girls and women. Endo also affects transgender, non-binary and gender-diverse people, but we don’t yet know exactly how many people in these groups are affected by endo. Symptoms can be very painful, difficult, and can affect a person’s quality of life by making it hard for them to go to school or work, to be social, active, and to enjoy their hobbies. Endo is a life-altering condition. It’s much worse and more serious than having a bad period.

- Endometriosis (endo) is a chronic condition where tissue that’s like the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) attaches to other parts of the body

- Endometriosis is usually found in the pelvis (the area below the belly button). It can happen outside of the uterus in other parts of the body too.

- Like the process of a period, the endometriosis tissue can become inflamed (irritated) by hormones

- Endometriosis can be very painful, and it can also create scarring inside the body, which may affect how your body functions

Can I catch endometriosis?

Endometriosis can start around the time a person gets their first period. It isn’t something you catch, like a cold, but it can run in the family. A menstruating person who has a close relative with endo is more likely to have it.

Delay to diagnosis

Many people with endo experience a delay to diagnosis. This means that when they first speak to a doctor about their symptoms, the doctor might not think that they have endo. Sometimes this is because the symptoms can look like other health issues. Understanding what could be a sign of a problem and when to talk to a doctor or nurse can help speed up the diagnosis process. Getting a diagnosis can lead to getting help.

And, because many of us are told that period pain is normal, some people with extreme pain, like endo, might not recognize that what they’re experiencing isn’t normal. They might not try to get medical help.

If you think something’s wrong, ask for help

Some of the symptoms of endo can be embarrassing or difficult to talk about, but there’s nothing to be ashamed of. Ask for help. If you’re worried about your period pain, speak to a doctor, nurse, parent, or elder in your community. You know your body best. Endo can be treated, but not cured. The earlier the diagnosis the better.

Hi, I’m Amira.

I’m 15 years old and I live with my family in Winnipeg, Manitoba. I used to love school, hanging out with my friends, playing hockey, and riding my bike. But, ever since I started getting my period a couple of years ago, my favourite things have become too painful to do most of the time. My cramps are so bad that they make me feel sick. Sometimes I can’t even get out of bed. At first, I was only in pain when I had my period each month, which was bad enough. But lately, I have cramps and aches when I’m not on my period, and not just below my belly button. Nothing helps, not even taking Advil or a hot bath.

I started missing hockey practice and school every time I had my period. Coach spoke to my mom about it, but Mama said it was normal to stay home during that “time of the month.” When I asked her if she used to stay home a lot because of her period when she was my age she said that being a woman was painful and refused to talk about it anymore.

I used to be a really good student. But now I’m tired all the time. I can’t focus. And some of this stuff is really embarrassing, especially the bathroom stuff. Mama says this is normal, but it doesn’t feel normal to me. I hate it. But, what can I do about it?

Endometriosis is treatable

While it can’t be cured, there are ways to treat endo so that people like Amira can get back to doing the things they love. The sooner endo is diagnosed the better, because if left untreated, it can cause infertility and chronic pelvic pain. Undiagnosed endo can become more serious, in some cases resulting in the need to remove pelvic organs.

Endo is typically treated with a combination of surgery, medications, other forms of care, and lifestyle changes. Doctors should talk to patients about their options. While some doctors have a lot of experience treating endo, not all doctors are experts in this area.

Options for managing endo are different from person to person and may include:

1. Medications

- There are different kinds of medications that can help with endo symptoms

- Everyone is different and not all medications will be a good fit for each person

- If you have endo, work with your doctor to find what will work best for you. You’re the expert on your body and you get to make decisions about it!

2. Expert endometriosis surgery

- A type of minimally invasive surgery using a camera and tiny instruments that look for endo

- Used to diagnose and excise (cut out) endo in the same surgery

- Performed by surgeons (doctors who do surgeries) who have special training in minimally invasive surgery so they can cut out endo

There are also natural ways and lifestyle changes to help manage the pain from endo, including balanced and healthy eating, pelvic physiotherapy, yoga and meditation, acupuncture, and good mental health support. Everybody’s different and what’s most important is to try things and find what works for you.

Speak up for your health needs

It’s Amira, remember me?

Well, I just couldn’t take it anymore. I didn’t want to be in pain all the time. So, after I missed another big hockey game with our rival school last month and let the team down, again, I worked up the courage to talk to a youth worker at school. I told her about how much pain I was in, almost all the time now. And, I told her what Mama said about how it’s normal for women to be in pain. I just can’t believe that this is normal period pain. It can’t be!

The youth worker was super nice about it, she listened to me and told me to see a doctor. She said I could go to the community health care centre where they might have a family doctor for me. She suggested I should bring someone I trust to the appointment so they could take notes for me and be there for emotional support.

I’m nervous, though. I don’t know what to expect when I speak to a doctor. What do I tell them? What do I ask?

What is a medical advocate?

It can take up to 10 years for people with endometriosis (endo) to get a diagnosis and start getting help.

The youth worker Amira spoke to had a great idea for her to bring a friend, family member, or someone she trusts to her appointment with a doctor.

Sometimes called a medical advocate, this person can be there for emotional support, to take notes and to ask questions. When you advocate for your own health, or for someone else’s, you’re communicating an important need and you’re making sure to get help.

It’s a good idea to do some prep work before an appointment with a doctor. Here are some ways Amira could prepare for her appointment to make sure she gets the help she needs.

She could:

- Track her symptoms and take notes

- Keep track of her menstrual cycle using an app or another method

- Write down her questions for the doctor

- Ask someone she trusts to come to the appointment with her as her medical advocate

- Bring a notebook and pen (or phone with notes app) to take her own notes about what the doctor tells her

You can always get a second opinion. This means that you go to a different doctor, nurse, or health professional about your health problem. Remember, you know your body best. If you think something’s wrong, especially if it’s keeping you from going to school and doing the things you love, keep asking for help. Keep looking for answers. You deserve to get help.

Learn more about endometriosis and other period-related health conditions:

The Endometriosis Network Canada

YourPeriod.ca

Period products: there’s a lot to choose from

There are a lot of period products out there now. It can be tricky to know which ones to use and when. It’s a good idea to talk to other people who get their period about what kinds of period products they use and what works for them.

Here’s a list that includes the period products out there today. You can use the internet to research products that may be new to you and to learn more.

Deciding which period products to use and when to use them is a very personal choice. And it can change over time. Some things to keep in mind when choosing period products:

Comfort: what works for one person might not work for someone else and it can depend on the kinds of activities they do.

Cost: period products can be expensive. Some products, like the reusable ones, are more expensive upfront, but save you money over time.

Sustainability: the environmental impact of disposable period products.

Convenience: it can take time to learn how to use and care for period products properly.

Accessibility: how and where to find period products.

What are they?

A small cup made of flexible material, like silicon. It catches blood to prevent leaks. Menstrual cups come in different sizes and shapes to fit different bodies. The cup has a small grip at the end to help take it out.

How to use them

Wash the cup with unscented soap and water, bend the cup while still wet, insert it into the vagina and release so that it opens and doesn’t have any folds in it. To take the cup out, find the grip at the bottom, gently squeeze the sides of the cup to break the seal and pull out, keeping the cup upright. Remove, empty, rinse, and reinsert the cup a few times a day so it doesn’t overflow.

When to use them

These are best to use on heavier flow days, but can be used anytime during a period, even while sleeping. Most cups can be worn for 10-12 hours before removing.

How to care for / dispose of them

Wash with unscented soap and water before, after, and between each use.

They’re reusable — you don’t need to throw them out.

Some people sanitize their cup in boiling water between periods.

What are they?

A piece of disposable material made of plastics with a cotton lining that absorbs blood. They come in different sizes and shapes for heavier or lighter flows.

How to use them

Unfold the pad from the packaging, peel back the strip on the underside of the pad, and place it sticky side down in underwear. Some pads have wings, or little tabs to fold under, and stick to underwear to help hold the pad in place. Change the pad every 3-4 hours.

When to use them

They come in different sizes for use on heavier or lighter days. Some are made specifically for overnight use while sleeping. Some people find pads uncomfortable when doing sports and they’re not made for swimming.

How to care for / dispose of them

Roll up the disposable pad, wrap it in toilet paper, and put it in the garbage bin or special bin for period products.

What are they?

A piece of disposable material made of plastics with a cotton lining that absorbs very light flows, like spotting. They come in different sizes and shapes, but are thinner than pads.

How to use them

Unfold the liner from the packaging, peel back the strip on the underside of the liner, and place it sticky side down in underwear. Some liners have wings, or little tabs to fold under and stick to underwear to help hold it in place. Change the liner every 3-4 hours.

When to use them

On light days, like at the very end of a period. Some people get spotting before or between periods and liners can be a good option.

How to care for / dispose of them

Roll up the disposable liner, wrap it in toilet paper, and put it in the garbage bin or special bin for period products.

What are they?

Period underwear: look and feel much like regular underwear, but they’re made to soak up blood. Many brands offer different styles, including boxers.

Reusable pads: look and work like disposable pads, but they’re made of fabric, are washable, and are made to be used again and again.

How to use them

Period underwear: wear just like normal underwear. For heavier flows, change underwear 1-2 times a day.

Reusable pads: place in underwear, fold wings underneath, and snap together. Change every 3-4 hours.

When to use them

Period underwear: some are made for heavier days, some for lighter days. On very heavy days, some people wear a menstrual cup or tampon as well as period underwear to avoid leaks. Some brands make period underwear for activities like swimming, dancing, and other sports.

Reusable pads: can be used just like disposable pads.

How to care for / dispose of them

Rinse period underwear and reusable pads in cold water and wring out before putting in the washing machine. They can be washed along with other laundry as long as they’ve been rinsed in cold water first. Hang to dry.

What are they?

A tube of fabric (usually cotton) made to absorb blood. They come in different sizes for different flows and bodies, and can be inserted with or without an applicator. A tampon has a string on one end to help take it out.

How to use them

Some tampons come with an applicator, which helps to insert the tampon into the vagina. Others don’t and need to be inserted using a finger. Depending on the heaviness of the flow, change tampons every 4-6 hours. To take it out, pull gently on the string.

It can be dangerous to leave a tampon in for more than 6 hours.

When to use them

Some people use tampons all through their period. Some only use them when they’re swimming, travelling, doing sports, or when their period is very heavy. You may want to avoid wearing a tampon to bed at night because you need to change them every 4-6 hours.

It can be dangerous to leave a tampon in for more than 6 hours.

How to care for / dispose of them

Wrap the tampon in toilet paper and put it in the garbage bin or special bin for period products. Don’t flush it down the toilet.

Not everyone lives in places and situations where:

- they can afford to buy the period products they need

- they can find the period products they need

- they have what they need to use and care for or dispose of their period products properly

Period poverty is a big problem in many places around the world, including in Canada.

Let’s think. Period.

Q: If you or someone you know is experiencing period poverty, do you know where you can get help? What could someone do if they:

- Q: Can’t afford or find period products?

- Q: Don’t know enough about periods to manage their own period?

- Q: Don’t have regular access to a washroom with a toilet and running water?

Period symptoms: what helps?

As we learned earlier, some people have uncomfortable periods, some people have pain at different points in their cycle, and some people have very serious pain that could be a sign of a health condition like endometriosis. If you get your period, it’s important to have ways to feel better when you have period pain or discomfort. If you don’t get your period, it’s good to be able to understand and know how to help someone who’s having period pain.

Here are some things that can help with period pain, discomfort, and difficult symptoms. Work in partners or small groups to add ideas you know or think could help.

Things that could help

Using a hot water bottle where it hurts (below belly button) or taking a warm bath

Things that might make it worse

Caffeine (pop, coffee, energy drinks)

Things that could help

Yoga or meditation

Things that might make it worse

Not getting enough sleep

Things that could help

Taking an over-the-counter medication like Tylenol or Advil when the pain is bad. Always use as directed. It’s important to speak to a pharmacist or trusted adult before taking any kind of medication

Things that might make it worse

Not being active or being too active

Things that could help

Eating a healthy, balanced diet

Things that might make it worse

Eating a lot of processed foods or too much sugar

If you get your period, you could track symptoms every time you get your period so that you know what to expect and how to feel better.

As we learned earlier, when period pain regularly keeps someone from doing the things they love, like going to school, being active, and spending time with friends, it can be a sign that something’s wrong. If period symptoms interrupt your life, that’s not normal. Health conditions like endometriosis need to be diagnosed by a doctor. It’s important to know where we can go to get help when we need it.

Think about the people, places, and things in your life that could help you or someone you care about to manage period symptoms.

Q: Who’s someone to turn to for help with period symptoms?

For example: my sister

Q: How could they help?

For example: I could talk to my sister about how I’ve been feeling extra sensitive during my period and she could comfort me by listening and sharing her experience with me.

Q: Where is somewhere to go for help with period symptoms?

For example: a website like yourperiod.ca

Q: How could it help?

For example: I could visit the site to learn more about periods and what to expect.

Q: What’s something I can do to help with period symptoms?

For example: go for a walk in nature

Q: How could it help?

For example: I could get some fresh air, some exercise, and some sunshine to help with my mood.

Periods are a part of life

It’s okay to be private about some things, but periods don’t need to be a secret. Many adults don’t talk about things like periods, sexual health, or sex. Maybe you don’t talk about this kind of stuff at home. That’s pretty common. The people who are raising you didn’t get the chance to read this workbook. They might not have had a chance to get comfortable having honest conversations about our bodies. But, things change. You’re allowed to ask questions, talk, and learn about this stuff. Your body belongs to you and it makes sense that you want to learn all about it.

It’s important to bring periods into everyday conversations to get rid of the unnecessary shame and embarrassment many people feel around having a period. And, there are some other less personal, but equally important reasons to speak openly and honestly about periods.

Let’s talk. Period.

- Remember Amira? How might period shame prevent her from getting help with her symptoms?

- And what about how much school and hockey Amira misses out on because of her difficult symptoms? If her period keeps her from doing some of the same things that other students (maybe those that don’t get a period) get to do, does she have the same access to opportunities as them?

Menstruation in the media

There’s lots of misinformation and disinformation out there about periods. Misinformation is when the facts are wrong. Disinformation is getting the facts wrong on purpose to mislead or confuse someone. And then there are things that are just bizarre, like commercials for period products that use blue liquid to represent blood. Why not use red liquid?

Ways to learn more

What do you do when you have a question about your health? Most of us turn to the internet for answers. And it’s often where we learn about things we might be too uncomfortable or embarrassed to ask another person about. But, it can be tricky to tell when the information you’re getting is true. Remember, there’s lots of misinformation and disinformation out there.

The best way to make sure that the information you’re getting is true, is to go to a reliable source. A reliable source means it’s information you can trust.

Here’s a checklist to help you tell whether a website you’re using to find answers to your questions is a reliable source:

- The address starts with “https.” The “s” means the website is secure.

- The address has a padlock symbol next to it. This means it’s a secure website.

- The website doesn’t have spelling or grammar errors.

- The website is easy to use and all of the links work when you click on them.

- The website looks professional.

- The website doesn’t have many pop-up or ads.

Another way to check if the information you find online is true is to look for the answer on a few different websites. If the websites look reliable and all say the same thing about the information you’re looking for, it’s probably true.

Let’s try it. Period.

- Q: Do an online search for the answer to the question “what are period cramps?”

- Q: Identify one reliable source from the list of search results. What makes you think it’s a reliable source? You can use the checklist above.

- Q: Check the answer on 3 reliable sources. What do they say? Do they all say the same thing?

- Q: Based on your research, what’s the answer to the question “what are period cramps?”

Make a promise to be period positive

Being period positive means talking openly about periods, avoiding negative language when speaking about periods, and advocating for your needs and the needs of others who menstruate. There are lots of ways to be period positive and you can learn more at periodpositive.com

As a group, make a list of ways you can practice being period positive. Consider writing your list on a big sheet of paper and posting it somewhere everyone can see it.

There are lots of ways to continue your learning about periods and about your health. In the last activity, we practiced doing safe online searches using reliable sources. The internet can be a good way to get answers to your questions, especially if you know where to look.

Here are some websites where you can continue your learning:

YourPeriod.ca: yourperiod.ca

A website from the The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) with in-depth information about periods, period-related health conditions like endometriosis, and reproductive health.

Period Positive: periodpositive.com

Ways to be period positive and links to educational content for teachers.

The Endometriosis Network Canada: endometriosisnetwork.com

More information about what endometriosis is, treatments, and other helpful resources.

Not everyone has the same access to the internet and devices. Depending on whether you live in a city, town, or more remotely, you may not have all of these places to learn more, but you can ask people you know, like a teacher, family member, or elder.

Q: Where else could you go in your community to ask your health questions?

Q: If you don’t have access to a doctor, nurse, or clinic in your community, who could you go to to ask your questions and learn more?

Here are some ideas:

- Teacher

- Friends

- Family

- Elders or spiritual leaders

- Who would you go to?

Menstruation is often called a period because it’s the period of time each month when a person with a uterus bleeds. The uterus is a triangle-shaped space in the body where a baby can grow during pregnancy. Most periods last anywhere from 3-8 days and happen once a month.

A taboo is something that a group of people or even whole societies and cultures avoid talking about because it may be seen as offensive, dangerous, or impolite.

Stigma is a negative way of thinking and talking about something that makes people uncomfortable.

Cisgender (cis) is someone who identifies with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender (trans) is someone whose gender doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth. For example, a trans boy is someone who was assigned female at birth but who knows themself to be a boy.

Non-binary person is someone whose gender blends aspects of being a man or a woman, or a gender that is different from being a man or woman.

Two-spirit is a pan-Indigenous term for someone who has both a female and male spirit. Some Indigenous peoples view two-spirit as a third gender or something in between female and male. It is a cultural, spiritual, gender, and sexual identity for some.

Intersex is someone born with a body that doesn’t fit into the traditional binary boxes of female or male. They may have both female and male organs and/or hormones. Almost 2% of the population is born intersex. Being intersex is a naturally occurring variation.

A vital sign is something doctors and nurses usually ask about at a check-up. A period is an example of a vital sign for someone who gets their period.

Puberty is a process most of us go through as we change from being a kid into an adult. Puberty is different depending on what kind of reproductive organs you have.

Reproductive organs are the body parts a person is born with that could one day make a baby. A vagina is an example of a reproductive organ.

To advocate means to publicly support something that’s important to you. When you advocate for your own health, or for someone else’s, you’re communicating an important need and you’re making sure to get help.

The uterus is a triangle-shaped space in the body where a baby can grow during pregnancy.

The vagina is a muscular, hollow passageway that starts at the vaginal opening and leads to the uterus.

The ovaries are two small, oval-shaped glands on either side of the uterus. They make and store eggs (ova) and hormones that control the menstrual cycle and pregnancy.

The endometrium is the lining of the uterus that thickens during the menstrual cycle and sheds each month if a person doesn’t get pregnant, resulting in bleeding.

When a person who gets a period is fertile it means that they can grow a baby inside their body.

Period symptoms are the things a person experiences, including how their body feels and also their emotions, before and during their period.

Endometriosis is a chronic condition where tissue that’s like the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) attaches to other parts of the body. Endometriosis is usually found in the pelvis (the area below the belly button). It can happen outside of the uterus in other parts of the body too. Like the process of a period, the endometriosis tissue can become inflamed (irritated) by hormones in the body. It can be very painful, and it can also create scarring inside the body, which may affect how your body functions.

A chronic condition is a health problem that lasts longer than 6 months and may become worse over time.

Infertility is when a person’s body can’t make a baby.

Chronic pelvic pain is pain in the area below the belly button that lasts for 6 months or more. The pain can be there all the time or it can come and go.

Pelvic organs include all of the organs in the pelvis (just below the belly button). For people who get a period, these include the uterus, bowel, and other organs.

Minimally invasive surgery is when doctors and nurses use special techniques and tools to perform a surgery that’s less painful and easier for the patient to recover from.

A medical advocate is someone who goes to a health appointment with you. They could be there for emotional support, to take notes, and to ask questions.

Period poverty is when someone doesn’t have access to period products, education or information about periods, and/or a washroom with a toilet and running water.

Financial contribution:

The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the views of Health Canada.

Clinical expert review by

The information included on this page is for educational purposes only and is not intended as medical advice. Where we reference websites, we do so for information purposes only. The Endometriosis Network Canada is not responsible for content on these sites.